ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORY EDUCATION

SECOND ROADSIDE HISTORY WORKCAMP 2023

I strongly encourage you to participate in the Polish-German workshops for young people organized, as last year, by MGOK BOLIMÓW AND VOLKSBUND based on the concept of peace education activities with the use of roadside elements of the historical landscape of the historical battlefield in the Rawka region proposed by the Roadside History Lessons Foundation.

Deadline: 25.07.-04.08.

Place of realization: BOLIMÓW and vicinity

The aim of the workshop called ROADSIDE HISTORY is historical and archaeological education, as well as activating reflection and activities of young people around the issue of WWI war cemeteries remaining on the territory of present-day Poland.

Many of these cemeteries (especially in central Poland) remain forgotten. Some of them have already been cared for and remembered, but some still bear little resemblance to the resting places of fallen soldiers. Although they should and out of respect for the fallen soldiers and in light of formal and legal considerations. Once again, young people from Poland and Germany, together with tutors, lecturers and residents of Bolimów and the surrounding area will have the opportunity to contribute to improving the state of preservation of a selected war cemetery and to learn about recent trouble war history, and both themselves and each other.

ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE EASTERN FRONT

(2020-2021)

(acronym: AEF, in Polish AFW)

Dear Colleagues,

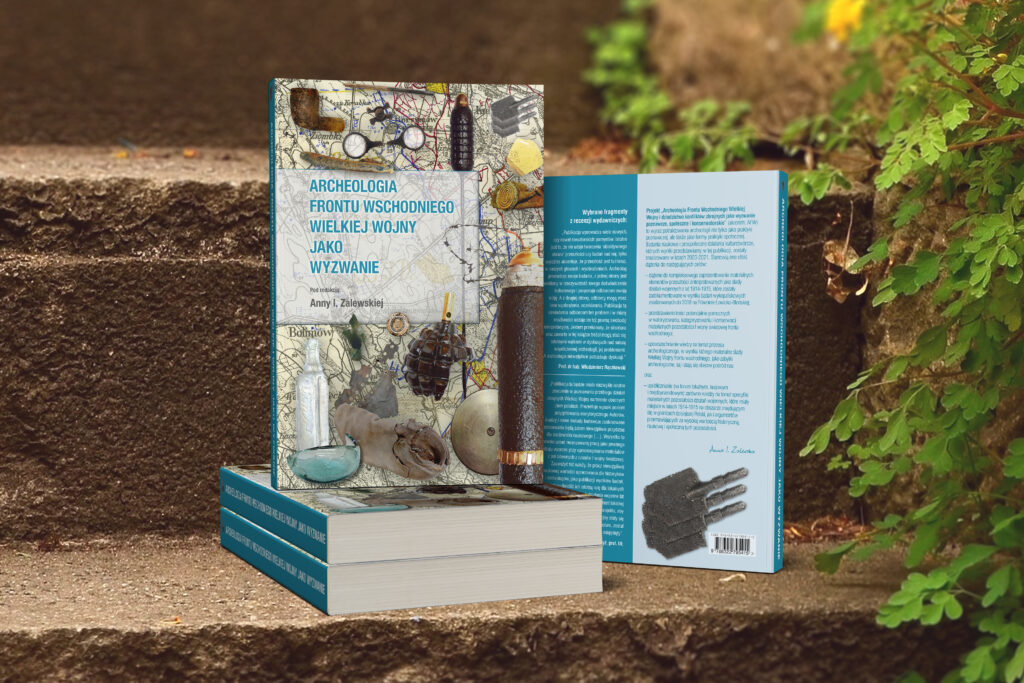

I am happy to inform that our newest publication is READY 🙂

A word of introduction

The content of this publication has the following objectives as their target:

– striving for a comprehensive presentation of material elements of the past interpreted as traces of military operations on the Eastern Front in 1914-1915 that have been documented as a result of investigations carried out until 2018 on the Łowicz-Błonie Plain;

– presentation of content potentially helpful in the valorisation, categorization and conservation of the material remnants of World War I of the Eastern Front;

– disseminating knowledge about the archaeological process, as a result of which the material traces of the Great War have become and are becoming present among us as archaeological finds,

and

– making public (on local, national and international forums) both the knowledge about the specifics of the material remains of the military operations that took place in the years 1914-1915 in the area located within today’s Poland, as well as the arguments for the high historical, scientific and social value of those remains.

This publication is a summary of the scientific project entitled Archaeology of the Great War Eastern Front and the legacy of armed conflicts as a cognitive, social and conservation challenge (acronym in Polish AFW). The project was implemented in the years 2020-2021 within the program of the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage of the Republic of Poland.

The implementation of goals chosen complements the process of analysing and publishing the results of research in the field of the archaeology of the Great War, carried out in the Rawka and Bzura basins, obtained mainly as the outcomes of the earlier (2014-2018) project entitled Archaeological Restoration of the Memory of the Great War. Material remains of life and death in the trenches on the Eastern Front and the state of changes in the post-battle landscape in the Rawka and Bzura regions (1914-2014) – Polish acronym APP, and of previous reactive pre-investment archaeological research (2005-2008).

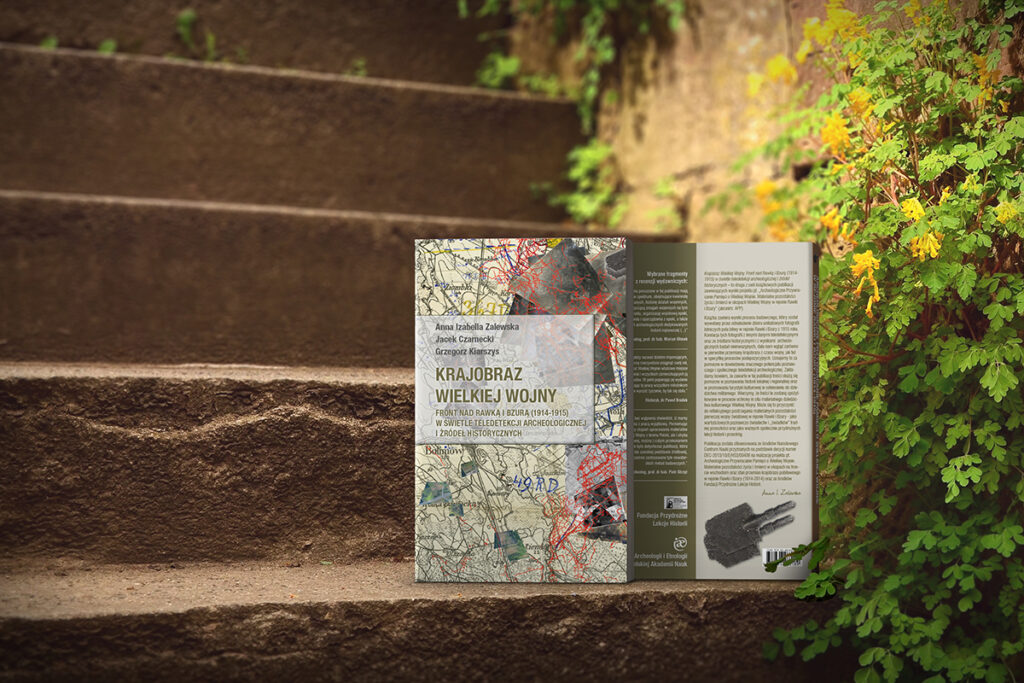

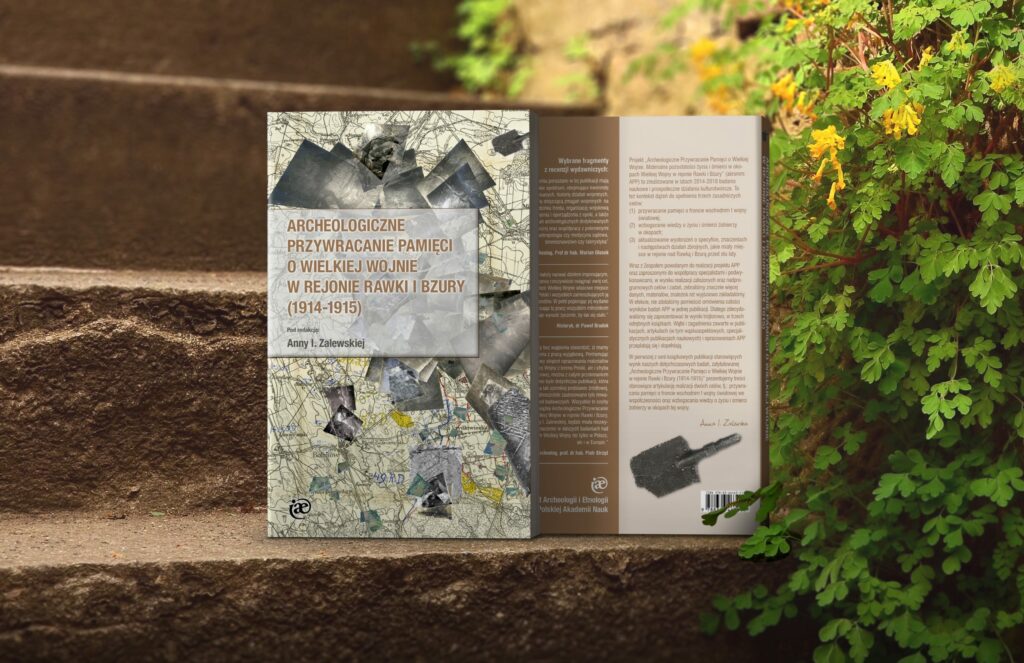

The results of the APP have already been partially published in the first of a series of publications in Polish: Archaeological Revival of the Memory of the Great War in the Rawka and Bzura Region (1914-1915). The contents of this work (Zalewska ed., 2019) had the goals of restoring the memory of the Eastern Front of World War I in the present day and enriching the knowledge about the material remains of the life and death of soldiers in the trenches of this War. In turn, the conclusions from the research on the features of battlefield landscape were included in a second Polish publication: Landscape of the Great War. The Front on the Rawka and Bzura (1914-1915) in the light of Archaeological Remote Sensing and Historical Sources (Zalewska, Czarnecki, Kiarszys 2019).

It seems reasonable to treat the combined message of these publications as creating favourable conditions for a better understanding of the contextualization of the archaeology of the Eastern Front of the Great War in central Poland providing the starting point for considering the cognitive and social challenges created by material remnants of the conflict, and discussing the legitimacy and importance of continued research, discovery and display of these material traces and especially their preservation and conservation.

This is the background for the present publication, the third in the series: Archaeology of the Eastern Front of the Great War as a Challenge. This takes a wider look at the properties of the remains referring to the warfare of the years 1914-1915 investigated with the use of archaeological methods as well as the relationships and connections of the people, things and places relating to this phenomenon and to their contemporary context.

The choice of the described issues in this volume is the effect of striving to obtain representativeness of the characteristics of the types of the different areas of relationships with the modern world of the material evidence of the military conflict a century ago and its aftermath, and which are accompanied by various social, cognitive and conservation challenges. The volume opens with an introduction to the complex issues presented from a methodological perspective. The main content of the publication has been divided into three parts.

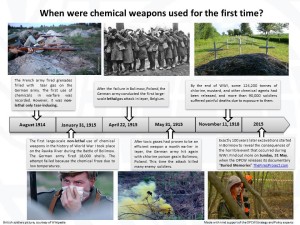

The first part gives an insight into the past and present social challenges that accompany the archaeology of the Eastern Front. The starting point is the characteristics of materials that were acquired by the fighting parties (very often at the expense of the local population) in connection with the War. By describing the things that are rarely found in archaeological contexts, the author refers to issues that are often overlooked in war studies, despite their significant pro-social potential. The next two chapters focus attention on the human losses suffered by the armies fighting in the territory of today’s Poland. The dramatic results of the use of poisonous chlorine, here shown through data on the first wave attack carried out on May 31, 1915 by the German army, give an insight into a wider problem of the numbers, or rather uncountability, of the victims of these chemical weapons. Indirectly, it shows the reasons why so many war graves and cemeteries remain unknown (inaccessible to us). Meanwhile, it is the graves of soldiers that are “the best sermons about peace” as aptly put by Nobel Peace Prize winner Albert Schweitzer. They are also places of cultural significance for contemporary culture and, as such, they should be provided with timeless protection and care with a view to the future. Also, other traces among us, testimonies left by the Great War, are significant for the culture of our times. These include traces of both tangible and intangible values.

Among the elements of the intangible heritage of the First World War are still current references of science, memory and contemporary culture both to the lost lives of the fallen soldiers and the barbarous use of chemical weapons and their effects on their victims. Chemical attacks were carried out many times in 1915 on the Eastern Front (regions now in Poland). An insight into this issue is also provided in the chapter by chemists invited to cooperate with archaeologists, who, by searching for traces of active chemical substances in samples taken from the battlefield, indirectly sensitize us to the still current problem of weapons of mass destruction.

The last chapters in this section deals with the problems related to the fallen soldiers and their resting places. They give insights into the processes of reconstructing the osteobiographies of the fallen and of finding and interpreting places where bones of fallen soldiers were found that are still not part of organised cemeteries.

The second part of the book discusses various types of cognitive challenges constituting the archaeology of the Eastern Front of the Great War. It begins with chapters important for the history of archaeological thought due to the fact that they provide an insight into the time in which the finds from the First World War were generally not documented and interpreted as archaeological sites. The change of attitude towards this type of monuments was the result of the rescue (pre-investment) excavations that were carried out in 2005-2008 on the Łowicz-Błonie Plain in advance of highway construction.

The following chapters present selected aspects of the results of the excavations that had taken place as part of the proactive archaeological research carried out in 2014-2018, aimed at the interpretation, identification, documentation, protection and pro-social activities marking the presence of the archaeological monuments. Using selected examples, the three main groups of archaeological sites examined as part of the planned research are presented: the resting place of fallen soldiers; the sites on which the relics of the rear-line infrastructure were identified and the sites where the elements of field fortifications including barbed wire were documented.

Then, by activating the content of archaeological and historical sources, various materials are presented that were used in the course of the hostilities of 1914-1915 on the Eastern Front by the warring parties. These finds have been presented in a systematic way, taking into account the main groups of raw materials and functional groups representative of the historic substance of the Great War of the Eastern Front. Attention was paid to the properties, meanings and roles of the ubiquitous metal. Metal relics were presented by discussing the remains of artillery ammunition, hand and rifle grenades and also items related to feeding the soldiers fighting in the Rawka and Bzura area in 1914-1915.

The last aspect is complemented by the archaeozoological characteristics of the bone remains documented in archaeological features. Then, the properties of archaeological relics made of leather, glass and ceramics are presented emphasising their connections with the soldiers, with civilians, and with the processes taking place in 1914-1915 and their consequences.

The third part of the publication presents problems resulting from conservation challenges in relation to the material remains of the Great War. These are challenges related to the massive quantities, but also fragility and poor condition of the movable finds, which can benefit a lot from the conservation process, as is demonstrated through the discussion in this volume of the conservation of the remains of artillery munitions. On the other hand, other challenges result from the considerable spatial extent of the archaeological features that are the traces of the warfare of 1914-1915. An insight into their properties is provided by remote sensing methods and GIS analyses, which turned out to be indispensable not only in studying these remains, but also in struggling to make them more widely known, with the aim of preserving and protecting the area of the analysed battlefield.

The volume is summarised by the chapters aimed at showing, on the one hand, the cultural potential of the historical battlefield landscape of the Great War (which can be used up, for example, in the field of reflective cultural tourism), and on the other hand, the very real risk of the loss of its in situ potential. The third part ends with the description of the manifestations of the practical application of archaeological, historical and anthropological knowledge in the protection of the traces of war (in the form of a protest).

The volume opened with a chapter that presents, from the methodological perspective, the essential elements of the structure of the archaeological process of the Great War of the Eastern Front. It ends with a presentation, systematization and valorisation of the evidence produced by the fieldwork and selected groups of finds. This comprises a series of tables that contain information on the examined archaeological sites and movable finds separated into groups according to raw material and function.

The main contributors to this publication were the members of the Research Team engaged in carrying out the AFW project, comprising (alphabetically): Angelika Bachanek, Dorota Cyngot, Jacek Czarnecki and Grzegorz Kiarszys whom I would like to thank a lot for this. The content presented in this publication also shows how fruitful the invitation of specialists from various fields and areas of specialization to analyze the collected data turned out to be. I would therefore like to sincerely thank all the authors of individual chapters who accepted the invitation to cooperate for their contributions. I am especially grateful to them for the discussions we had of the artefacts and other results of the fieldwork, and for help in resolving numerous dilemmas in selecting material for study and preservation from the many mass finds and their valorisation, and for all their efforts during the unfavorable circumstances caused by the Covid-19 pandemic.

I would also like to thank all the other people and institutions who contributed directly or indirectly to the achievement of the objectives of the AFW project, including the Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, in particular to Ms. Beata Herbaczyńska-Stankevič from the Centre for Scientific Research for her professionalism, great heart and mind, sense of support and security that she gave me in a difficult moment and to the Institute of Archaeology of the Maria Curie-Skłodowska University in Lublin and the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw.

My greatest debt of gratitude, however, is due to Dorota Cyngot and to my husband and son. I am also grateful to Kateryna and Jan Zalewscy for donating precious time so that I could devote this period to finalizing this project’s goals.

Special thanks are also due to Małgorzata Multan-Sieczka, Director of the Primary School in Humin, the involvement of which is exceptional in the context of our research. This school was founded in 1908 for children who were then taught by a shoemaker, and some of the classes were held in private homes. Thanks to the involvement of the local community of parents, a brick school was built in 1913, but unfortunately it was completely destroyed in the course of military operations in 1914-1915. In 1917, on the site of the destroyed school, a small wooden building was erected, which, however, could only accommodate some students, the rest had to study in makeshift rooms in private homes. The scale and long-term consequences of the damage done to this region during World War I is indirectly shown by the fact that this situation lasted until 1955. Only then, were the inhabitants of Humin able to build another brick school. It was within the walls of this building that now works Ms Małgorzata, one of the greatest history teachers I have had the opportunity to meet while working with her students. It is the existence of groups like this that gives the hope that the significance of the physical remains of the Eastern Front of the Great War will continue to be recognized and appreciated by citizens of the region in the future, and this will make it possible to meet the challenges accompanying their existence and survival, allowing a constructive approach to those challenges. This living hope is much greater than even the growing number of new record cards with data on the previously neglected features of archaeological landscape of the First World War held in the National Sites and Monuments Records.

Project name:

“Archaeology of the Eastern Front of the Great War and Heritage of Military Conflicts as a Cognitive, Social and Conservation Challenge”

Polish abbreviation: AFW

Main objectives: making known to the public on the local, national and international forum, the knowledge about the archaeological process as a result of which material traces of World War I on the Eastern Front are raised to the rank of archaeological monuments;

Providing arguments for the establishment of “archaeological sites” in the formula developed by the monument protection;

comprehensive study of research results concerning archaeological findings and movable and non-movable historical objects interpreted as traces of military actions in central Poland in the period between 1914 and 1915 as part of the research conducted till 2018

developing, on the basis of a specific group of findings and movable and non-movable historical objects (over 20,000 items and the area of 250 sq km) from the period of World War I

a proposal for an interpretation key that would be potentially helpful in valorization, categorization and conservation of the remains of World War I

2020 | 35 | 243-273

&

ARCHAEOLOGICAL REVIVAL OF MEMORY

OF THE GREAT WAR

(2014-2018)

(acronym: ARM, in Polish APP)

The projects ARM & AFW are dedicated to the material and social memories of those who were suffering during the time of the Great War and those who experienced and still experience the presence of the remains of the Great War

The main objectives of the ARM project implemented in 2014-2018 were as follows:

- reviving the memory of the Eastern Front of the Great War on the Rawka and Bzura rivers and encouraging a reflection on the agency of landscapes marked by warfare as material warnings for the future;

- deepening our knowledge on the lives and deaths of entrenched soldiers and the interactions between people and the landscape as occurred both during the war and in its aftermath;

- recognizing the unknown history and material memory of the use of chemical weapon in 1915 in Central Poland – the gas-scape*;

- updating our preconceptions about the specificity and consequences of the conflict that erupted in the area of the Rawka and Bzura;

- locating and delimiting war cemeteries from the period of the Great War and located in the studied area;

- documenting and interpreting the current state of preservation in terms of the unique landscape (gas-scape) that witnessed the birth of total war and the era of mass-scale death that followed;

- ensuring due protection for the unique material warnnings such as the terrain forms burdened with the troubled past and war cemeteries for the benefit of future generations.

-

Assumptions:

The ‘Gas-scape’ goes far beyond the mere theatre of war, the stage on which ‘killing culture’ was born. It is also the scene of on-going, post-depositional and hopefully pro-social (cognitive, artistic, pop-cultural but also non-human and so on) processes. It is tilted towards the future, as a warning, but also an inducement to think, with the support of archaeology, of reconciliation. It can also be seen as a touchstone of the actual potential of ALS when it is applied to the cognitive process as well as other pro-depositional processes – providing support to protect the in situ existence of that complex, causative and meaningfully palimpsestic landscape scarred by World War I.

Depositional Processes on the Eastern Front ‘Gas-scape’

The war in the region we are studying saw at least four times the deployment of chemical weaponry by the Germans as they found themselves unable to breach Russian defences in any other way. The first deployment, on 31 January 1915, was driven by wider strategic considerations as preparations for the winter campaign in Mazuria were well under way. Attacks on the Polish bend of the Vistula had been reduced to a few skirmishes:

To keep Russians on their toes and convinced that the attack was continuously ongoing, the 9th Army was ordered in late January to attack with full force in the area of Bolimów. With that in mind, the High Command issued 18,000 shells for our use, gas ammunition to be precise. It is important to understand, in the context of those times, that such a vast amount of ammunition was something quite extraordinary.

The artillery shells were filled with the so called ‘T-Stoff’ (xylyl-bromide) agent and Ni-shrapnel containing an irritant (‘sneezing powder’). The attack was regarded as unsuccessful, with failure blamed on the low temperature (-3 degrees Celsius) which curbed the destructive power of the ‘T missiles’ (Hoffman [1923] 2013: 52). However, as General Ludendorff recalled in his war memoirs, the main objective of keeping the Russians too preoccupied to take an interest in the German attack in East Prussia was accomplished:

“We took several thousand soldiers captive; beyond that, the tactical success was limited. However, the impression that the attack had on the Russians was great. … We had achieved what was expected in the area of strategy”.

The Germans’ next attempt to use gas took place four months later, shortly after the first large-scale military use of poisonous gases near ypres in Belgium on 22 April 1915. On 31 May 1915 chlorine was deployed in the area between Majdan and Zakrzew, where the Germans placed 1,200 steel canisters along the frontline and released 240 tonnes of heavier-than-air chlorine. This was done by a special gas unit, Pionier-Regiment Nr. 36 led by Colonel Goslich, which, like Pionier-Regiment Nr. 35 led by Colonel Peterson, consisted of scientists, chemists and chemical industry workers.

for further details see:

Zalewska A. (2016) The ‘Gas-scape’ on the Eastern Front, Poland (1914–2014): Exploring the Material and Digital Landscapes and Remembering Those ‘Twice-Killed’

Zalewska A. (2013) Roadside Lessons_ Roles, Meanings and Efficacy of the Material Remains of The Great War at former Eastern Front.

Those interested in further details,

CONTACT: Anna I. Zalewska (azalew@op.pl)

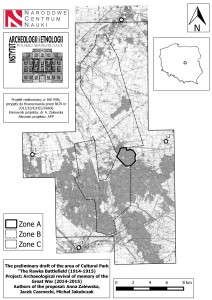

Research area is extending over approximately 330 square kilometres of landscape located in the region of Mazowsze. Administratively it is the part of the Mazowieckie and Łódzkie Voivodeships. Geographically it is the central part of the Łowicko-Błońska Plain:

ARM’s area of resaerch (2014-2018)

The area in question is a moraine denudation plain, which forms one of the flattest landscapes in the Mazowsze region – a fact that undoubtedly contributed to its selection as the site of early chemical weaponry use on the eastern front. The river Rawka cuts meridionally across the research area. Still unregulated, in many places, particularly between the villages of Kamiony and Bolimów, the river follows a deep ravine with banks as tall as 10 meters. Past Bolimów and all the way to the river’s estuary, the Rawka ravine becomes wider, shallower and significantly less steep.

In 1915, it was the river of Rawka itself along with its ravine that constituted the “No Man’s Land” along the section of the frontline between the village of Kamion, through Ruda and Budy Grabske, and eventually to the village of Ziemiar and the former Mogiły manor, at which point the frontline swerved to the east and away from the river. Between Wola Szydłowiecka and Humin, the “No Man’s Land” included a section of a minor watercourse called the Chełmna. From there, to the village of Sucha, No Man’s Land overlapped with a stretch of arable land and ignored the other small watercourses in the area. The landmarks that may help to delineate the former frontlines in the area include the road between Humin and Kurabka as well as the manor in Borzymówka.

To the north of Bolimów, two small watercourses eventually flowing into the Bzura cut across the research area from the north-west to the south-east. The frontline would later stabilise against an approximately 2.5 km stretch of the tiny Sucha rivulet located somewhat to the south. The Pisia river flowing in roughly the same area played no part in the frontline stabilisation of 1915. The last section of No Man’s Land of particular interest to us covered the area of the Bzura ravine from the mouth of the Sucha near the village of Zakrzew and all the way to Sochaczew. The river follows an almost perfectly meridional channel here with only a slight deviation to the east. Approximately one third of the research area is currently forested (some 110 km2).

A reconstruction of the pre-war landscape based on a copy of a 1:126,000 Russian map (a so-called “three-verst map”) dated around 1914 reveals a forested area of approximately 120 km2 which almost perfectly overlaps with the forests existing nowadays.

The Great War resulted in a number of violent transformations of the surrounding landscape.

The Archaeology of Modern Conflicts have over the last decades been systematically implemented in western European countries, mainly in Belgium, France and England.

The results of such studies not only enrich our knowledge of the events that transpired a century ago, but also deepened respect for the material relics of the past, awoken sensitivity, and shaped historical awareness of those interested in it.

In ARM project we have elaborated the concept of socially useful archaeology (such as archaeology of reconciliation and / or archaeology as the antidote to vandalism and / or archaeology which provides the stimulations for reflection, a.o. by exposing / presentyfying spatially extensive warning monuments.

Projects of this type inspire considerable social interest and naturally translate to efforts aimed at advancing the due protection and preservation of the material relics of the recent past. However they can also stimulate mutual understanding between descendants of the once fighting each other sides via reflective approach to remains of war including cultural tourism, educational projects etc.

Meanwhile in Poland, the problems of World War One Archaeology (or more generally: issues related to the material and mental remains of 20th c.’s conflicts) continue to be marginalised.

Our research team is created to answer the urgent need to establish a new sub-discipline of archaeology dedicated to the problems, phenomena and concerns that have been so far neglected to the great detriment of science, society and the historic substance of relics of the recent past.

For indeed, we are now witnessing a greatly accelerated process of ongoing decay of the material remains of 20th century conflicts, which has intensified over the last ten years due to progressing industrialisation of forested and rural areas, as well as through the activities of so-called detectorists. Members of the research team devoted to the performance of these innovative research comprise a group of specialists deeply convinced of the viability of the efforts to study and preserve the material remains of the Great War, and of the need to disseminate the popular knowledge of this unique turning point in history.

Members of the team were carefully selected on the grounds of their competence, field-work experience, and willingness to participate in introducing a new quality to the field of archaeology in Poland.

We have started the fieldwork at the beginning of August 2014 and will finish our project with the publication in 2018.

Anna Zalewska

(Projects Originator and Principal Investigator)

Source: Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW)

The significant Others, about the project:

“A hundred years ago Bolimow, a small peaceful town in Poland, was the site of a bloody World War I battle. Encouraged by its success at Ypres, the German Army used chlorine gas as a weapon at Bolimow – the first time chemical weapons were successfully used on the Eastern Front. A hundred years have now passed. Committed to never repeating the horrific experiences of World War I and elsewhere since then, 190 countries are working under the Chemical Weapons Convention to rid the world of chemical weapons. Despite having so far eliminated almost 90% of declared stockpiles, including in Syria amid a bloody conflict, allegations of chemical weapons use persist, and the spectre of chemical terrorism is looming ever larger. Has humanity really learnt the lessons of Bolimow?

This event will start with a screening of the short film Buried Memories. The documentary talks about a lethal chemical attack during a World War I battle at Bolimow, Poland, and the work of an archaeologist to make this historical event known. The screening will be followed by a discussion on emerging challenges for the disarmament of chemical and other inhumane weapons.”

The movie “Buried Memories”, part of #TheFiresProject has been released! It will bring you back to the Bolimów battlefield where 100 years ago the German army used chemical weapons for the first time on the Eastern front, shortly after the first large-scale lethal chemical weapons attack in Ieper, Belgium.

A hundred years later, Anna Zalewska, a Polish archaeologist, decided to reveal this area’s tragic past that before seemed buried and forgotten. Discover what happens when archeology meets drama: #TheFiresProject

http://www.thefiresproject.com/buried-memories/